We’re still often asked what makes a good password and why a lengthy string of random letters, numbers and symbols is the best. However, a prominent US body has recently altered its recommendations, which may perhaps make creating passwords slightly easier.

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is a US government agency that provide the guidance that other US government agencies rely on. Because of this lofty position, when they make recommendations, it is generally recognised worldwide.

Back in 2016, NIST released their previous guidance on passwords which has been the basis for many agencies and businesses password policies. However, following four years of work, they have released new guidelines for password creation.

Previous guidelines recommended forcing employees to change their password every 45 days, and make sure those passwords include numbers, capital letters and special characters, causing them to be virtually immemorable.

So, what do they recommend now?

- Long passwords are still a must, with a minimum of 15 characters. Yes, 15. This can be reduced to 8 if the login is coupled with multi-factor authentication.

- Password resets should be done via a separate channel. E.g. an emailed password recovery link, a stored recovery code or an SMS / WhatsApp time-limited code.

- Do not reuse passwords. This isn’t new but worth repeating. They also state to avoid using any password that has been in any previous breach.

- Login sessions should be time-limited (so you can’t login to a website today and come back in a few days without logging in again)

What do these mean in real terms?

There are some interesting insights here; complexity requirements are officially “out”. Surprisingly, forcing complexity onto humans actually weakens security by making passwords more predictable – think of logins such as “Password1!”. When users must add special characters they often follow common patterns that make it easier for attackers to guess. Of course, if you are using a password generator this shouldn’t be a problem.

Length matters

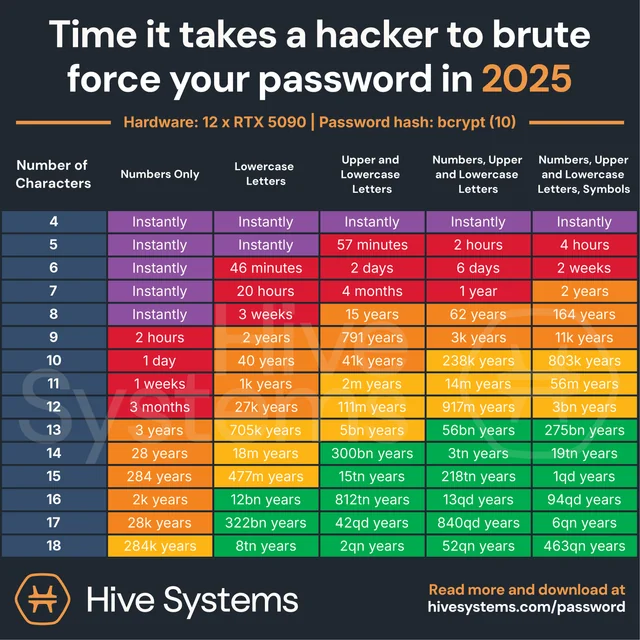

From a computer science perspective this makes a lot of sense – the longer a password, the more attempts, and thus time, that any brute-force attack must go through in order to crack the password.

In a simple example, a 6-character password made just from letters could be brute-forced in around 321 million guesses. That may sound a lot but at modern compute speeds is very do-able and remember that most times the attacker will get lucky before they guess the final possible permutation. If you double the length of that password without adding any complexity you are not just doubling the time it would take an attacker, in fact the time goes up exponentially to around 99 quadrillion guesses.

Hive Systems created this chart, logging the time taken to hack a password of different lengths and complexity.

Any password generator will compute a suitable length password. In cases where a password generator isn’t feasible simply create a lengthy phrase – “MyCatIsAliceMyDogIsBob” is counter-intuitively strong because of its length and most attackers wouldn’t know exactly what the phrase was (at the time of writing it’s also never knowingly been in a breach).

Is your password choice already known to attackers

There are a number of services which offer to check if a password is known to be in attackers’ lists (called dictionaries) and thus will be tested regularly, Have I been Pwned, supported by Cloudflare, allows you to check if the password you chose is known to attackers.

You can also enter your email address into https://haveibeenpwned.com/ to see if any of your accounts have been exposed in previous breaches and sign up for notifications going forward.

Passwordless

While passwords and passphrases are not going away any time soon, the world is starting to look beyond them and the challenges that they face security-wise.

The use of 2 factor authentication, especially when coupled with a code sent via an alternate means which expires after a period of time, really increases the complexity for an attacker to breach your accounts.

Passwordless logins such as PassKeys are now starting to become mainstream, you may have noticed when logging into Amazon on a modern mobile device that you will now be prompted to create a passwordless login, these work entirely differently by creating a challenge that the device uses to compute an asymmetric cryptographic response where the private component is stored on your PC/phone and the website only ever knows the public component. This allows the PC or device, once confirmed by means of a fingerprint or PIN, or similar, to generate a response that could only have been generated by that device.

As this is quite resistant to phishing, re-use and brute force attack, these make an exceptionally strong login means but currently have portability limitations (i.e. your phone and PC may not be able to share the same login unless they are from the same provider, e.g. Apple) however there are specifications being agreed that will allow greater interoperability going forward.

Physical tokens such as the YubiKey which can take a fingerprint and generate a unique output that cannot be replicated without physical access to the key and fingerprint are also a technology to watch as features such as NFC make what was once a very inconvenient and expensive way to authenticate, much easier and more affordable.